Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

Yo Ho Ho and a bottle of rum for me. Pirates and rum have been intwined for centuries. During this time, colorful stories of rum induced adventures on the high seas have fueled many legends and stories. Considering the golden age of piracy was between 1650 and 1720, it makes perfect sense to connect these figures with rum since its beginnings and rise to popularity were around the same time. Historical evidence such as broken rum bottles found in noted pirate hangouts such as Port Royal further tighten the connection. Over the years, movies, books and other media have further connected the two and ingrained it into popular culture. While we would like to think that pirates exclusively imbibed on rums, the truth actually is: they would drink pretty much any thing they could find....and rum was easy to find!

Offering fringe benefits during the hiring process to entice workers has been a common practice for centuries. The English Navy is no exception. One of the more popular "fringe benefits" of joining the Royal Navy became known as the "Rum Ration" or "Daily Tot". In its beginnings, however, rum was not the offered beverage. Beer, Brandy and basically whatever spirit was available in the port of calls was the offering. According to rum historian and Master Rummelier® Matt Pietrek, author of the book, Modern Caribbean Rum. “When the British Navy first started commanding the oceans in the late 1500s, if you think about the containers they had at the time, they were just wooden casks, where any liquid would be stored,” Pietrek said. “Water by itself, in wooden casks in a hot tropical climate, was going to go bad pretty quickly. Even beer would go bad because the alcohol content wasn’t high enough. It was really only a distilled spirit, that the alcohol basically prevented it from spoiling.” The other reason for the tot was to keep the sailors’ morale up in brutal conditions. As rum became plentiful in the Caribbean and began to be imported in large quantities to England, it soon began to become commonplace on the ships.

In the 18th century, each sailor (aka "Jack Tar") was issued around half an Imperial pint of rum a day, which translates to about ten ounces. Between 11 am and noon, a call of "Up Spirits!" would echo through the ship. This was the signal for all men to gather on deck to receive their "daily tot" of rum. If the order "Splice the Mainbrace" is given, the sailors would get an extra bit of rum to celebrate something such as a victory.

The United States Navy actually had a similar program as the British Navy, with a daily half pint of spirits issued to sailors. This practice was begun in 1794 and was slowly phased out beginning in 1862 and finally being banned in 1914.

The Royal Navy was faced with a dilemma: They had promised the sailors a ration of rum each day, however, the commanding admiral, Edward Vernon, "violently opposed strong drink in any form and cursed its ill effects on the morals of his men." Realizing that he couldn't completely eliminate the "daily tot", he instead ordered that it be diluted with water. Since his nickname was "Old Grog" due to the grogram jacket that he donned, this rum mixture became known as grog. The name caught on and is still used today!

Another tidbit of history, George Washington's older half-brother, Lawrence, served on Vernon's ship HMS Princess Caroline in 1741. He named his Virginia estate "Mount Vernon" in honor of his former commander, a name that was retained by George Washington.

When Admiral Horatio Nelson was killed at the Battle of Trafalgar, his body was taken back to England for a hero’s burial. The famous corpse was stuffed into a cask of brandy to preserve it against decay on the trip. A legend arose that the body had actually been preserved in rum—and that sailors being sailors, Nelson’s battle-seasoned ratings had seen no reason to waste the rum that had preserved the admiral’s body. Grog now had a new nickname, “Nelson’s blood.”

During the 17th and 18th centuries, alcohol was considered safer to drink than water. Particularly, rum was preferred over other beverages such as beer and cider since it was easier to transport and more shelf-stable. It also became a commonly used form of currency. Industrious entrepreneurs also found that the plentiful supply of cheap molasses coming into the American Colonies could be distilled into the more profitable and popular spirit known as rum. This "currency" became so popular that it actually drove the economy of many cities such as Boston.

Eventually, a trade "triangle" was developed - Rum from the Colonies was exported to Great Britain and Africa who, in turn, exported slaves for labor for sugar production to the Caribbean Islands, who then exported raw molasses to the Colonies.

The first rum distillery appeared on what we now know as Staten Island, NY in 1664. As of 1770, there were over 150 rum distilleries in New England alone, and the colonists, collectively, were importing 6.5 million gallons of West Indian molasses, and turning it into five million gallons of rum.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, though, most rum would have been produced for domestic consumption. Many colonists would have had stills in their homes and would make alcohol for “medicinal purposes.” Apparently, there was always some to serve to neighbors and visitors including the preacher, though.

One of the most famous - and tasty - rums during this time was produced in Medford, Massachusetts. The location was popular because of its close proximity to the docks and several producers began to set up distilleries in the area. The first of four distilleries was started in 1715. Rum distilling in the area continued until prohibition and its rums have now become legendary amongst rum history buffs.

In towns throughout the Colonies in America, taverns became the epicenter of all social gatherings. Though segregated based on class, they all featured the most popular item on the menu -Rum! Multiple cocktails were created by innovative mixologists and became common as travelers shared the recipes.

The taverns became such an important part of the culture, laws were enacted in colonies such as Connecticut that required that a tavern be built when a settlement reached a certain size.

During breaks in religious services at nearby churches, thirsty parishioners would flock to the taverns to warm up and have a few drinks. This became such a distraction that church leaders enacted rules forbidding the drinking of alcohol - except for medicinal purposes. Expectedly, many church-goers suddenly developed ailments!

In these taverns, patrons would drink and discuss how unhappy they were about being suppressed. Many discussions about revolution and rebellion were probably fueled by rum. Taverns were supposed to be limited in number, but tavern owners would pay-off politicians who would go to speak in them and get votes.

It appears that a ration of rum wasn't an exclusive treat for sailors in the Royal Navy. During the Revolutionary War and other conflicts, the practice of rewarding soldiers - or enticing them to join - with rum and other spirits was commonplace.

Around 1755, during the French and Indian War, Ben Franklin was tasked with forming a militia to provide for the defense of Pennsylvania's inhabitants along with building forts. To recruit soldiers, he offered daily rations of rum - around twice the amount that the Royal Navy offered its sailors! Franklin noticed that the troops were always punctual when lining up to receive their twice-daily rations of rum.

During the Revolution, George Washington apparently freely dispensed rum and other spirits to the troops to boost morale - a tactic he learned during elections to persuade voters. In June 1779, Washington informed a General McDougall: “I have written to the Commissary urging him if possible to have a pretty good stock of rum at the forts to supply more constantly the fatigue parties.” Washington, along with many others, felt that rum aided in awakening tired soldiers ...and probably induced an extra amount of bravery as well!

The US Navy issued spirits to its sailors beginning on March 27, 1794 before being discontinued on July 14th, 1862.

During the Colonial Era, Rum was by far the drink of choice due to easy access and affordable price point. Rum, along with cocktails utilizing it, were a staple on menus in taverns throughout the colonies. By one estimate, colonists consumed 3.7 gallons annually per head by the time of the American Revolution.

Due to several factors including the increased enforcement of a tax on molasses which increased the price along with westward expansion (it was much easier to grow corn for whiskey than ship molasses barrels on wagons), rum's popularity eventually began to decrease. It was eventually replaced by whiskey as the drink of choice.

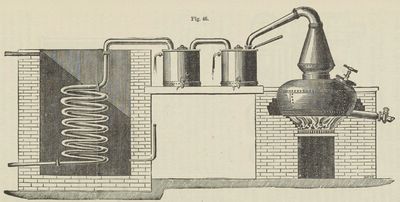

Invented by William Pontifex in 1797, this type of still is now generally used for rum production in the West Indies and elsewhere. The still is of copper, with a discharge pipe and cock, and a manhole for cleaning, &c. The still is shown set in brickwork and heated by fire, but sometimes it is fitted with an outer casing or jacket of iron, and steam passed between the still and the jacket--the heat necessary for distillation being thus obtained without the direct action of fire. On the top of the still is a conical head of copper, with a neck and arm leading to the next part of the apparatus, which consists of two copper cylindrical vessels, usually called "retorts " by the distiller. Each retort is fitted with a discharge cock and manhole, and in the best construction the top or cover is a few inches below the top of the sides, leaving what is termed a "water chamber." To the retort next the still a small pipe is attached, through which cold water is run to the water chamber, and discharged on the other side, as shown. The same thing is also done with the second retort. The use of these water chambers will presently be seen. The arm pipe that enters the top of the first retort is continued to within a few inches of the bottom. The pipe from the first to second retort is taken from the top of the first, but is continued down nearly to the bottom of the second, in the same manner as the arm pipe in the first retort.

https://digital.sciencehistory.org/works/qf85nb36v/viewer/h989r357r

Copyright © 2019 Royal Rum Society™ LLC - All Rights Reserved.